I Was Not a ‘Muslim Commissioner’: Identity Must Never Eclipse Integrity

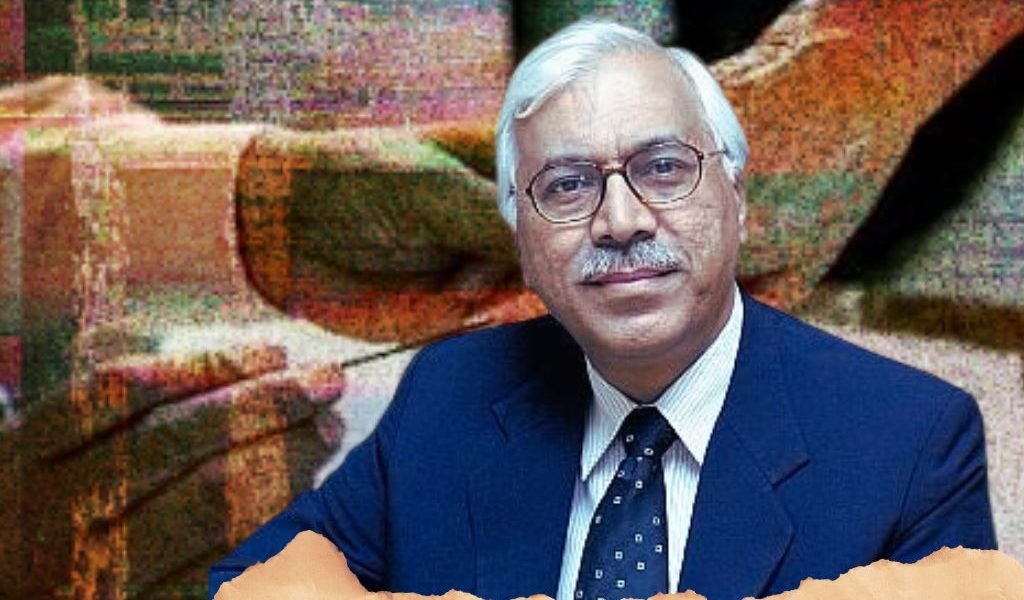

S.Y. Quraishi | 29 October 2025

When identity replaces duty, institutions unravel – a public servant recalls why creed never defined his commission.

When elected representatives of the world’s largest democracy resort to communal slurs in public discourse, it’s not just an individual who is maligned–the very idea of India is bruised.

Recently, I was referred to by an honourable Member of Parliament not by my name or office, but as a “Muslim Commissioner”. The term was not used innocently. It was intended to diminish my professional legacy, to communalise my constitutional role, and to stoke a dangerous us-versus-them narrative in a country whose soul rests on pluralism.

Let me state it plainly: I was not the Muslim Chief Election Commissioner of India. I was the Chief Election Commissioner of India, who happened to be a Muslim. The distinction is fundamental.

By reducing a public servant to their religious identity, the honourable MP did not merely insult me – he insulted the very idea of a neutral and independent Election Commission. He sought to tarnish a constitutional role with the grime of religious profiling, thereby suggesting that religious minorities, no matter how diligently they serve the Republic, can never be trusted as neutral custodians of public institutions.

This is the kind of dangerous framing that corrodes democracies from within.

This kind of labelling is not just about me. It is part of a broader pattern where Muslim identity is increasingly framed as a political provocation rather than a fact of life in India’s composite culture. When an MP uses the floor of Parliament or the megaphone of social media to prefix someone’s religion before their designation, he is not merely targeting one individual. He is signalling to a wider audience that Muslims are to be viewed with suspicion even when they serve in the highest constitutional offices.

It is worth recalling that the Election Commission of India has historically been seen as one of the most trusted institutions in the country. Its credibility is hard-earned – built over decades by men and women from every religion, caste and region. To now attempt to taint that legacy with communal hues is an assault on the institution itself.

If every Election Commissioner is to be viewed through a communal lens, what then remains of institutional integrity? If the integrity of a CEC is to be judged not by the elections conducted under their watch but by their religion, we are inching closer to a majoritarian theocracy, not a constitutional democracy.

But India is not built on majoritarianism. It is built on the principles of pluralism. Our democracy, with all its imperfections, remains one of the most inclusive experiments in self-governance the world has seen. To serve this democracy is to rise above the narrow confines of identity and act in the interest of all Indians.

Let us also ask: why now? Whmy this sudden resurrection of identity politics in the realm of public service?

The answer is both simple and chilling. In today’s climate, where polarisation is an electoral strategy and disinformation is a daily tool, dissent must be discredited – and the easiest way to do so is by “othering” the dissenter. For Muslims in public life, the price of public service is perpetual suspicion. You may serve the nation for decades, but speak out once – and you will be reminded of your religion.

It is a matter of record that during my tenure (2010–2012), the Election Commission took several pioneering steps to strengthen Indian democracy. We cracked down on black money in elections, introduced measures for voter education through the SVEEP programme, and rolled out significant voter registration reforms. We conducted elections that were widely praised for their efficiency and impartiality. I was not accused of bias then. To the contrary, I was then referred to by Mr Arun Jaitley as “one of India’s most mature and credible CECs”, and by Mr Gopalkrishna Gandhi as “one of the most remarkable CECs we have ever had, or likely to have”. Incidentally, Mr Gandhi has the best pedigree in the country, being the grandson of Mahatma Gandhi on the paternal side and of C. Rajagopalachari on his maternal side. The ‘honourable’ MP’s words, on the other hand, reveal something truly puny.

But years later, when I speak critically of government policies or defend democratic principles, my religion is suddenly invoked.

I worry, moreover, about the message this sends to young Muslims – to young people of all identities – who aspire to serve the nation. Are we telling them that no matter how honestly they work, no matter how scrupulously they follow the law, they will always be judged by their birth and not their merit? That no achievement is immune from slander if your surname or prayer mat does not match the dominant narrative?

Let us also not forget that constitutional values must be defended by all. Silence in the face of bigotry only normalises it. I am grateful that many citizens, journalists and political leaders across the spectrum have spoken out against this attack – not for my sake, but for the sake of decency in public life. But the defence of pluralism cannot be episodic. It must be sustained, principled and collective.

S.Y. Quraishi was Chief Election Commissioner of India from July 30, 2010 to June 10, 2012, and author of An Undocumented Wonder: The Making of the Great Indian Election (2015).

This article was originally published on The Wire.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.