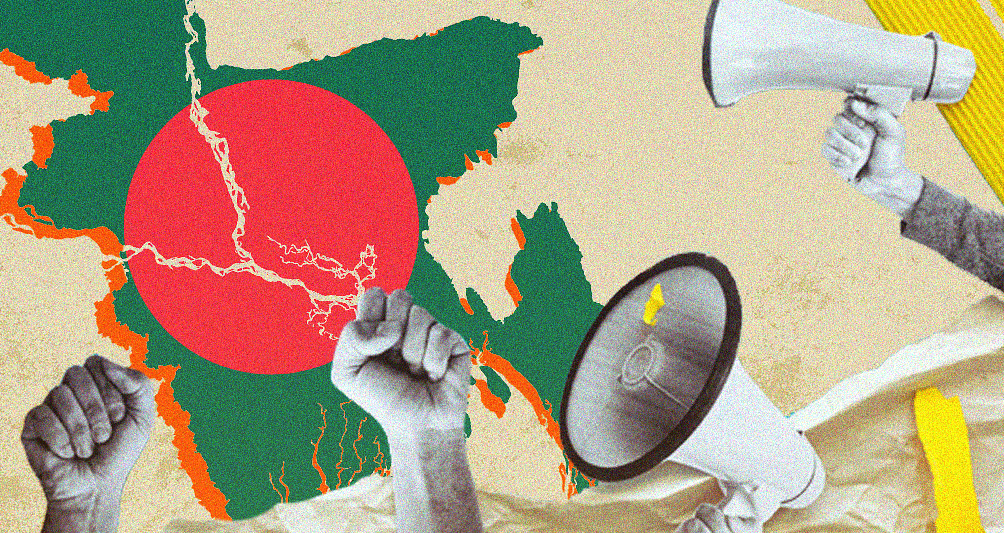

Our Civil Society Needs to Do More to Challenge Power Structures

Zillur Rahman | 25 April 2024

If the treatment of Nobel Laureate Dr Muhammad Yunus is any indication, Bangladesh's independent civil society is currently in great peril. Over the last year, human rights defenders, demonstrators, and dissenters have been met with harassment, physical aggression, detainment, and maltreatment by the authorities. Additionally, journalists who reported on government misconduct were subjected to persecution. Presently, anyone who attempts to criticise or protest against the ruling party is harassed through the use of draconian laws such as the Cyber Security Act and is also publicly branded as a mouthpiece for the opposition, regardless of their actual stance or motivation.

Furthermore, in its myopic struggle to preserve and consolidate its power base, the government is undermining key democratic institutions. This agenda is reflected in the wording of upcoming laws, such as the Data Protection Act, which have a broad tendency to weaken judicial and parliamentary oversight instead of super-powerful regulatory bodies and executive wings of the government.

The people are losing their power to change the laws that govern their lives.

It is unclear now if Bangladesh will ever see a government that chooses to decentralise power. The stagnant nature of the two-party politics in Bangladesh means that a solution to democratic decline will most likely not come from any one political party, but rather from the activism of the common citizenry, the vigilance of the independent news media, and the effective guidance of Bangladesh's independent civil society all combining to engineer the ideal circumstances that allow democracy to flourish.

However, to actualise its true potential of guiding the nation towards democracy, civil society in Bangladesh must orient itself under certain priorities.

The fact of the matter is that the people of Bangladesh have a fundamental lack of awareness of civil rights and liberties. To rectify this, Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) must act as pivotal sources of information and play several essential roles.

By forging strategic alliances and collaborating with other entities, CSOs can work together to devise innovative, lasting solutions and advocate for inclusive educational, knowledge, and policy frameworks. At the grassroots level, they can bolster citizen empowerment and foster environments conducive to learning, thus amplifying the community's voice and ensuring it is heard and considered in the decision-making process.

Lack of transparency and accountability is perhaps the fundamental reason behind the rampant corruption in Bangladesh. Without the existence of a reliable barometer for determining the long-term effects of policies, state actors never face the consequences of designing bad policies and making mistakes in decision-making. Civil society must employ a range of strategies to ensure governmental accountability, scrutinise the commitments made by the government, and assess them against the real-life experiences of citizens. They must conduct independent inquiries and report their findings, shedding light on discrepancies between promised services and their actual delivery. Through advocacy, CSOs must push for reforms and changes that stem from their investigative reports.

Bangladeshi CSOs also need to be active participants in policy dialogues, advocating for the inclusion of diverse stakeholder perspectives. They must exert influence on policy formulation by offering evidence-based recommendations and engaging directly with policymakers. Fostering citizen participation in governance, and encouraging active involvement in elections, public debates, and consultations, thereby ensuring that government actions align with the populace's needs and desires, are crucial. Moreover, CSOs ought to use legal avenues like the Anti-Corruption Commission and the judiciary to challenge government actions.

One of the most significant shortcomings of Bangladesh's civil society is its inability to effectively engage with the government on the policy advocacy level. CSOS needs to establish a comprehensive advocacy strategy that outlines specific goals, target demographics, and methods. This strategy should be grounded in an in-depth analysis and comprehension of pertinent issues. All advocacy must include the proposition of alternative policies to those of the government, the private sector, and other institutions. Utilising their own data, CSOs should formulate alternative policy proposals grounded in evidence.

CSOs also need to actively engage a broad spectrum of stakeholders—ranging from local community members to experts and fellow NGOs—to collect a variety of viewpoints and forge a consensus on policy alternatives.

Moreover, by establishing partnerships with other organisations, including international NGOs, CSOs can secure the necessary backing and resources to craft and advance alternative policy solutions. These collaborative efforts are crucial to enhancing civil society's capacity to contribute meaningfully to the nation's policy landscape.

Last but not least, CSOs in Bangladesh must take on the mantle of being vital defenders of citizens' rights. They must meticulously document human rights violations and amass evidence to substantiate their assertions. This aids in heightening public awareness, propelling advocacy for reform, and serving as legal evidence. CSOs can offer a spectrum of support to vulnerable individuals, including legal aid, psychological counselling, and other specialised assistance to human rights advocates, victims of rights violations, and marginalised or specifically targeted demographics.

Civil society must champion the cause of marginalised and disadvantaged groups, such as garment workers, and exert pressure on decision-makers at various levels—state, non-state, and international—to formulate and maintain policies that safeguard human rights. Through training programmes and the cultivation of local networks, CSOs can enhance the public's understanding of human rights and stimulate collective activism. They must also be prepared to initiate or support legal proceedings against human rights infringements, thereby pursuing justice.

The road ahead for Bangladesh's civil society is long and hard. And doing the right thing is often the hardest path. We must acknowledge that Bangladesh still has a long way to go before the promise of a democratic republic is realised. But we must also remember that democracy is the birthright of all Bangladeshi citizens. This right is enshrouded in the constitution, "The Republic shall be a democracy in which fundamental human rights and freedoms and respect for the dignity and worth of the human person shall be guaranteed, and in which effective participation by the people through their elected representatives in administration at all levels shall be ensured."

As long as the civil society of Bangladesh believes in the spirit of these words, there is still hope. But we must brace ourselves for the road ahead.

Zillur Rahman is the executive director of the Centre for Governance Studies (CGS) and a television talk show host. His X handle is @zillur

This article was originally published on The Daily Star.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy