Maldives Walks A Diplomatic Tightrope with India

Urmika Deb | 05 February 2024

On 4 January, three officials from Maldives’ Ministry of Youth Empowerment, Information and Arts criticised India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to India’s smallest union territory, Lakshadweep.

They labelled Modi a ‘puppet of Israel’, a ‘terrorist’ and a ‘clown’, prompting a public backlash in India and calls to boycott Maldives as a tourist destination. Hashtag #BoycottMaldives quickly trended online and the social media frenzy soon escalated into a diplomatic row between the two nations.

Maldivian president, Mohamed Muizzu, known for his pro-China sentiments, further aggravated tensions by snubbing India and making his first state visit to China after an official trip to Turkey. While the Maldives’ government suspended the loose-lipped officials, Muizzu’s shift towards more China-friendly foreign policies raises concerns about the balance of international relations in the region.

If the Maldives government drifts closer to China, and if its relationship with India remains strained, there may well be strategic and economic consequences for both India and the Maldives in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR).

India and Maldives have a complex historical relationship, primarily influenced by Maldives political leadership. Despite historical ebbs and flows, India has often been the first to respond to crises in Maldives including intervening in the 1988 coup against President Abdul Gayoom, and recently providing $250 million in financial assistance.

In 2009, Maldivian President Mohammad Nashid strengthened ties with India, signing a comprehensive security agreement allowing an Indian military presence in Maldives. Indian forces conducted search and rescue missions and joint patrols. They also monitored Chinese illegal fishing in the Indian Ocean in response to an increase in incidents from 372 in 2020 to 392 in 2021.

India-Maldives relations were strained between 2013-2018 by President Abdulla Yameen’s ‘India Out’ campaign aligning Maldives with China to lessen India’s influence over his country’s security. Chinese investments through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and general trade flourished with Chinese tourist numbers rising from 60,000 in 2009 to 360,000 in 2015. Yameen’s China-friendly policies led to high indebtedness and then the leasing of 17 islands to China.

Maldives foreign policy shifted again in 2018 with President IbuSolih’s ‘India First’ campaign, which restored India’s strategic position as the primary security provider to the IOR.

President Mohamed Muizzu’s election in September 2023 brought back Yameen’s ‘India Out’ campaign which was likely supported by political disinformation and online amplification. A report by the European Election Observation Mission (EU EOM) revealed that Muizzu’s ruling coalition of the Progressive Party of Maldives (PPM) and People’s National Congress (PNC), ran disinformation campaigns across social media platforms, including Facebook and Twitter, to influence public opinion and manipulate election results. The report states that their campaign included anti-Indian sentiments, based on fears of Indian influences and anxiety regarding a presence of Indian military personnel inside the country.

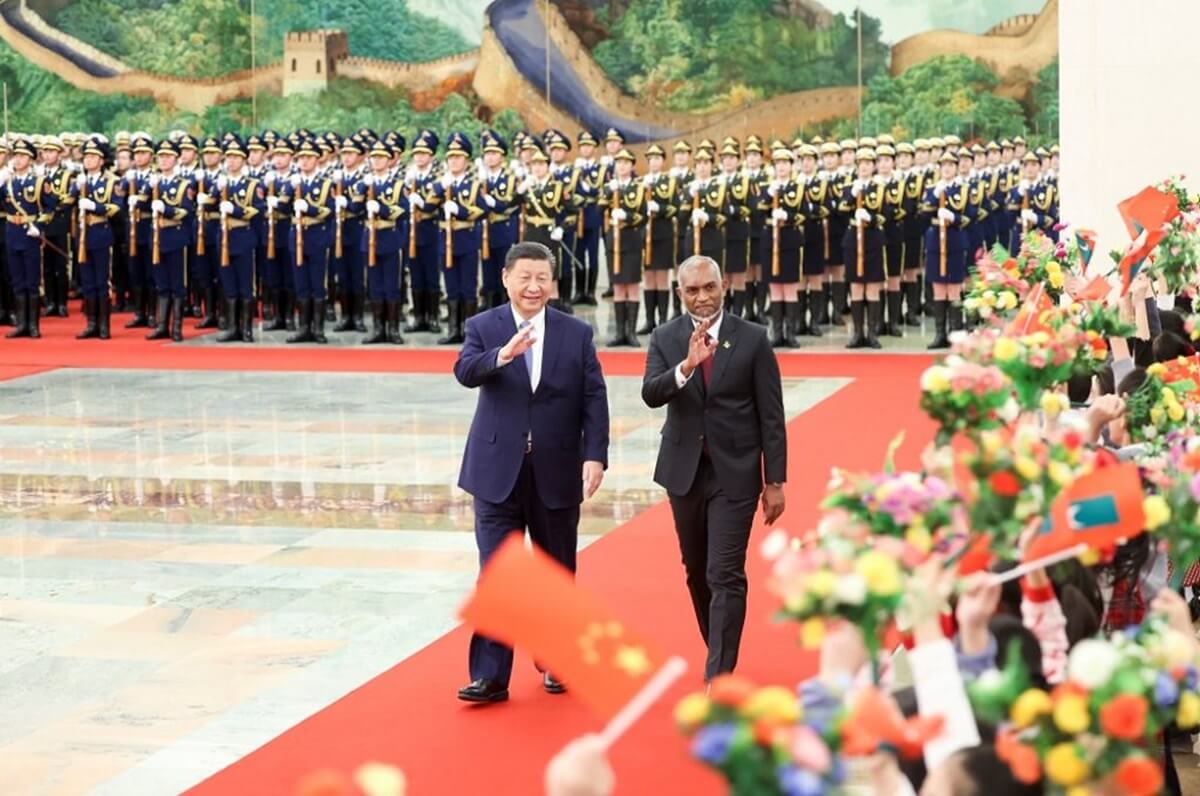

Since coming to office, President Muizzu has dramatically reset Maldives’ international relations. He broke tradition by visiting China before India. He requested the withdrawal of Indian troops by 15 March 2024 and signed a USD$37 million deal with Turkey for reconnaissance drones to replace the gap to be left by the withdrawal of Indian security. To decrease reliance on India, Maldives plans to import staple foods from Turkey and explore alternative sources of pharmaceuticals. During Muizzu ‘s recent five-day visit to China in January 2024, he and Xi Jinping signed 20 agreements spanning disaster risk reduction, fisheries, increased digital economy investment, joint acceleration of the BRI, and tourism among others.

So, why might the Maldives’ rapprochement with China be of concern to both Maldives and India?

If Muizzu merely switched Maldives’ economic dependency from India to China, he would drag his country further into the debt trap. Maldives’ share of Indian tourism increased from 6% in 2018 to over 14% in 2022. By turning away from India, Muizzu risks losing a major chunk of tourism revenue (accounting for 28% of Maldivian GDP in 2023) generated by Indian travellers to the islands. Recognising that 90% of the Maldivian economy is dependent on tourism-related activities, Muizzu has now urged China to ‘intensify efforts’ to send more of its tourists to Maldives. Increasing Maldives economic reliance on China will only further Beijing’s goals in the region.

And Turkish drones alone cannot match the vital role played by Indian troops in Maldives’ security. India, a long-standing ally since the 1988 coup, not only assisted in various operations but also provided crucial aid during the 2004 tsunami and 2014 water crisis in Male. Despite President Yameen’s attempts to engage with China and Pakistan, India continued to fulfill 70% of Maldives’ defence training needs.

Allocating $37 million for Turkish drones from a strained budget raises concerns about the project’s viability in a growing debt crisis. The money will buy Maldives at most five or six Bayraktar TB2 drones. While Maldives is aiming for a more sovereign foreign policy and does not intend replacing Indian troops with forces from other nations, it may still struggle to monitor the exclusive economic zone around its archipelagos with a limited number of drones and a small military.

From India’s perspective, China’s engagement with the Maldives adds to the pressure New Delhi faces in protecting its interests in the Indian Ocean. In this era of geopolitical contestation, having increased Chinese influence in its backyard is not welcome given that Sri Lanka is already enmeshed in debt-trap diplomacy and Pakistan’s dependence on China has increased through the BRI initiative.

Islamic radicalism in Maldives poses a security threat to India and other neighbouring countries. Maldives provided the highest number of foreign fighters per capita to the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) terror group. That reached its peak during Yameen’s presidency from 2013-18. The political leadership has been accused by some analysts of turning a blind eye to the extremist recruitment to secure votes. Extremist gangs organising out of Maldives lured young men into their gangs in the name of religion, promising them a better future, a sense of purpose, and material wealth. As an example, the 2022 attack on Indians during an International Yoga Day event organised by the Indian High Commission in Maldives highlighted the threat which persists despite efforts by international partners such as Japan which granted 500 million yen (US$4.5 million) to Maldives to boost its counter-terrorism capabilities. Despite some attempts to reintegrate families of extremists, the rise of anti-India sentiments in 2024, coupled with Muizzu ‘s emphasis on Islamic values, raises India’s concerns about heightened terrorism.

A push to shift the focus of tourism from Maldives to India’s Lakshadweep islands may have unintended environmental consequences. Indian investors have already made plans to set up 50 luxury tents and more permanent resorts, and the hashtag #ChaloLakshadweep (‘Let’s go to Lakshadweep’) is trending on social media.

The Lakshadweep islands are undoubtedly beautiful, but they are smaller, unexplored, and underdeveloped in terms of infrastructure, internet connectivity and manpower compared to Maldives. While one could argue that a boost in tourism might drive economic development, environmentalists have raised concerns that large-scale human interference would strain existing capacities, generate waste and exacerbate climate change, endangering the island’s fragile marine ecosystem and threatening livelihoods. It urges prioritisation of environmental risk assessments and sustainable infrastructural plans to head off a development frenzy driven by the social media feud over the Maldivian officials’ comments about India’s prime minister.

Considering that Maldives is a geopolitical hotspot, and India seeks to maintain strategic influence in the IOR, it is important that both nations recalibrate their actions and responses to better tackle the existing situation and reinforce mutually beneficial ties.

Urmika Deb is a researcher in the Cyber, Technology and Security program at ASPI.

This article was originally published on The Strategist — The Australian Strategic Policy Institute Blog.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.