Iran’s Anti-Veil Protests Have Already Succeeded

Sajjad Safaei | 25 September 2022

The Islamic Republic is no stranger to protests—but this time, they’re leaving a permanent mark.

Iran is in the midst of a series of spontaneous nationwide protests triggered by the death of a young woman shortly after being taken into police custody. Iran has experienced such waves of protest before. But this iteration is likely to leave the country permanently changed.

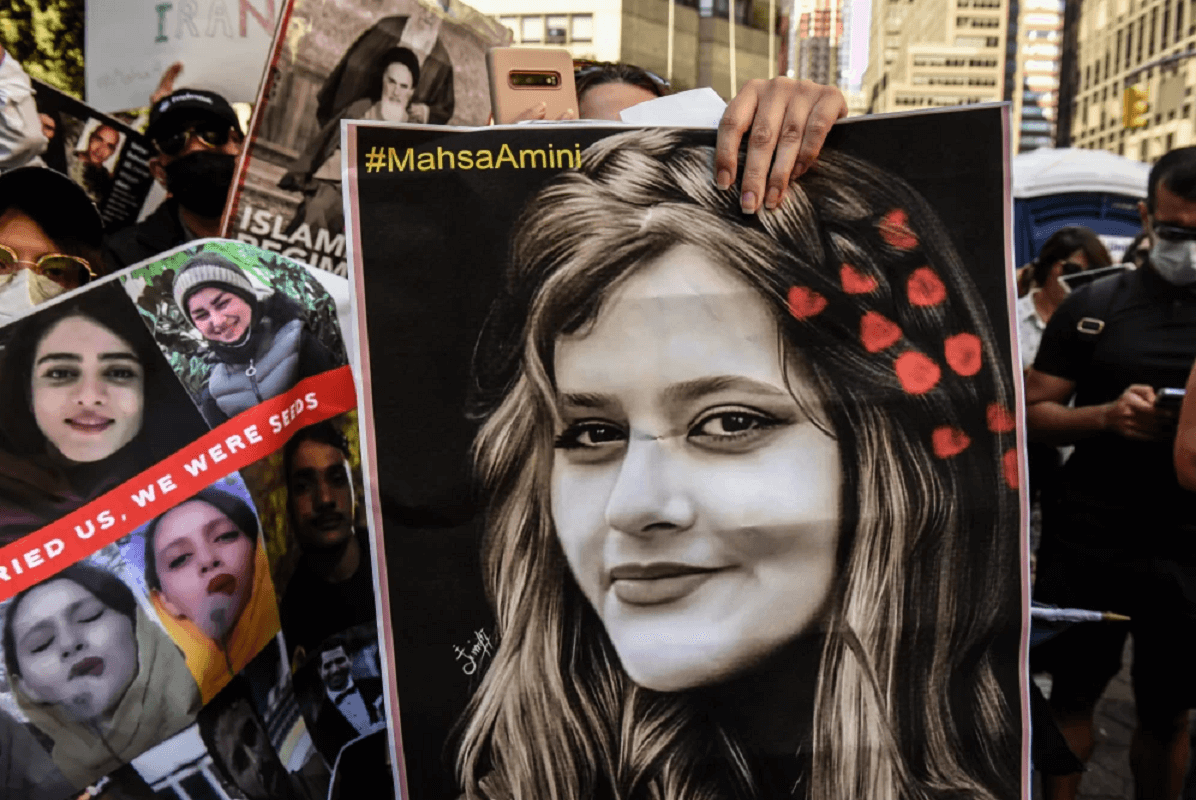

Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old woman from a small city in Iran’s Kurdistan province, had been visiting the country’s capital, Tehran, when she was detained, before her brother’s eyes, by the so-called morality police (gashte ershad or “guidance patrol”) for her “inappropriate” attire. According to the Tehran police, it was during her detention that Amini “suddenly” developed “heart problems” and was rushed to hospital, where she later died. (Her family vehemently denies claims that she had any preexisting condition before her detention.) The undisputed facts undermine the government’s claims to legitimacy: A young, healthy woman died while detained by a police force dedicated to enforcing laws that the vast majority of Iranians either oppose or resent.

The blatant evidence that a woman’s failure to cover a few strands of hair can upend her right to security, life, and freedom has shocked Iran’s conscience, including among those who may adhere to the state’s idea of an “Islamic hijab” but oppose mandatory hijab-wearing nonetheless. Cries of “Woman, Life, Freedom” have reverberated throughout Iran in since Amini’s death.

Iran has had previous public controversies over the compulsory hijab. But these protests mark a significant shift—the first time since the 1979 Islamic Revolution that a wide spectrum of parties and civil society organizations have openly called for an end to either mandatory hijab laws or the police patrols enforcing those laws. The issue has also drawn reactions from a very broad range of prominent political and religious figures, celebrities, and athletes.

These protests represent the first middle-class protest movement that has emerged in Iran since the Green Movement in the aftermath of the widely disputed 2009 presidential election. But there are important differences between the two.

First, in terms of size: There is no indication that the current protests have drawn anywhere near the number of people who took to the streets in 2009. Furthermore, the 2009 protesters were of diverse ages, whereas the current protagonists are overwhelmingly young. “They are mostly from the younger generation who may have only heard of the Green Movement. They would have been children or in their teens back then,” the sociologist and pro-reform activist Mohammadreza Jalaeipour told me. “They are fearless, direct, and brave, but also angry,” he added, “they are not monarchists. They want freedom and democracy.”

Another distinct feature of the current protests is the presence of very young women at the forefront. In many of the protests, women appear to outnumber men and do not seem afraid of being seen without hijab, even in the presence of security forces.

There have been many clashes between security forces and protesters, and multiple protesters have already been killed. But the crackdowns have not been as severe as the last round of protests over gas price hikes in November 2019. The full gamut of Iran’s security apparatus has not yet been deployed, although that could change. Indeed, authorities have already begun rounding up journalists as well as political activists, in particular. (Jalaeipour, who had been a vocal critic of the mandatory hijab law, is among those arrested.) Access to the internet as well as social media platforms such as WhatsApp and Instagram have also become limited.

Although the current protests were triggered, and are animated by, the frustrations over compulsory hijab, protesters are also channeling other pent-up grievances toward Iran’s ruling elites, such as the mismanagement of an economy reeling under U.S. sanctions, a crisis of political legitimacy exacerbated by the flawed legitimacy of the June 2021 presidential elections, and the increasing stifling of civil liberties.

As evinced by the outburst of public indignation triggered by Amini’s death, her case is not seen as an isolated incident but the visible tip of an iceberg of injustice, humiliation, indignity, and oppression routinely felt by countless Iranian women intercepted by the so-called guidance patrols charged with enforcing Article 638 of the Islamic Penal Code: refusing to comply with state’s conception of “Islamic hijab” in public spaces is a criminal offense punishable by flogging, incarceration, or a fine.

Though both the article in question and the state’s discourse on mandatory hijab are infused with religious undertones, governing women’s bodies has its roots in worldly rather than spiritual aspirations: political power. It was during the first years of the 1979 Islamic Revolution that religion and religious symbols such as the hijab were weaponized in the interest of purging rival revolutionary factions from politics.

More than four decades after the Islamic Republic embarked on the Sisyphean enterprise of bureaucratizing a very narrow definition of Islamic morality, with an almost obsessive focus on women’s appearance in public, mandatory hijab as well as the institutions set up to enforce it have failed veritably at forcing the state’s interpretation of “Islamic hijab” on Iranian women.

Instead, this encroachment on women’s liberty has gradually sown resentment in the hearts of millions of Iranian women and their families—resentment not only toward a dehumanizing law but also toward the state as a whole. Countless videos now course through social media showing the humiliating way Iranian police officers routinely manhandle women into vans before they are taken to detention centers to be “guided” and “educated.” Such encounters are at best stressful and patronizing, and at worst lethally brutal.

It is also counterproductive. In the face of such repression, women’s voluntary adherence to the state’s ideal hijab has not increased but drastically decreased over the last few decades, something even authorities openly acknowledge. Support for the hijab law and the morality police is even lower than the rates of public compliance. Even among the shrinking number of women who do adhere to the state’s strict interpretation of Islam, mandatory hijab and the morality police do not enjoy widespread support.

President Ebrahim Raisi, who had earned a reputation as a conservative while overseeing the judiciary, seems to acknowledge this discontent. He suggested during last year’s presidential race that he would end the patrolling of women’s attire. Indeed, there is now clear evidence that he was aware that any close association with the patrols had the potential to lose him the election.

Iranian leaders often boast, rightly so, that in a region rife with instability, they have been able to shield Iranian citizens against external security and military threats such as the Islamic State and the country’s regional rivals. But Amini’s death has shown that, as long as Iran’s ruling elites insist on enforcing the anachronistic revolutionary relic of mandatory hijab, the state’s relationship to its citizens will continue to devolve. So long as the state treats a few strands of hair as legitimate grounds for robbing a woman and her entire family of a sense of security, its public legitimacy will always be at risk—and Iran’s political establishment will always be on the precipice of a security crisis of its own making.

That’s why Iran’s ruling elites would do well to make concessions on the hijab issue—if not for the sake of the Iranian people, at least for their own sake. It remains to be seen whether the current protests will lead to the complete abolition of mandatory hijab and the policing of women’s attire. But they have already achieved what would have been unthinkable not long ago. From now on, it will be costlier for the Iranian government to punish women for something the vast majority of Iranians do not consider an offense, let alone a crime.

Sajjad Safaei is a postdoc fellow at Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology.

This article was originally published on Foreign Policy.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.