Gen Z Revolution in Retrospect

Parvez Karim Abbasi | 29 January 2026

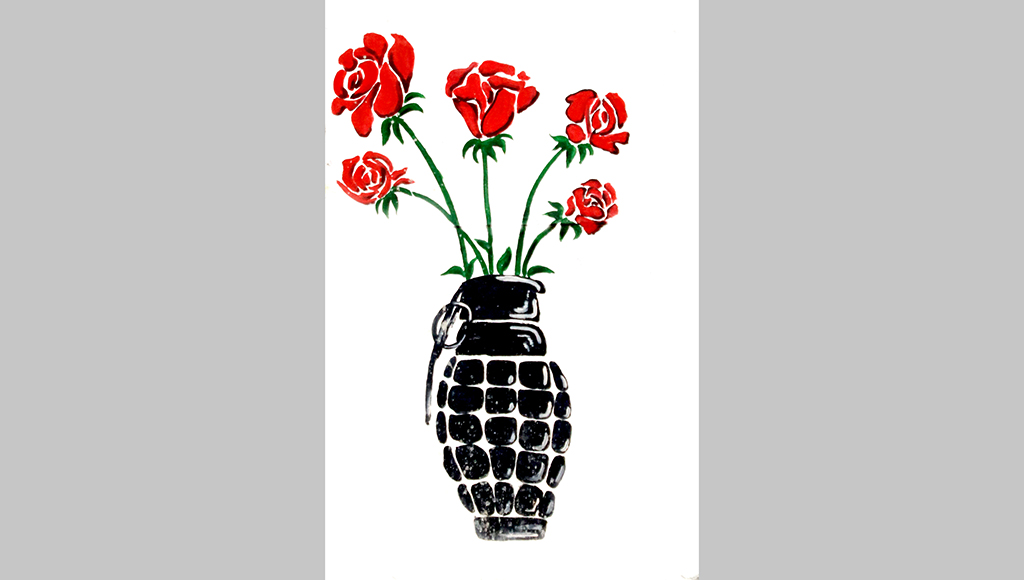

REVOLUTION- seldom has a word in the English lexicon stirred such conflicting emotions and ignited initial adulation and subsequent detraction in equal measure. The term has been romanticised, idolised, glamorized, sensitized, sanitized, duplicated, replicated, examined, analysed, criticised, rejected and re-evaluated. Change in times, change in material and spiritual circumstances, change in availability and access to information, change in modes of governance necessities re-evaluation of revolutions. This is what provides a febrile ground for contestation between pundits and experts about the respective merits and demerits of revolutions across history.

Within a span of roughly three years or less, a series of Gen Z led revolutions have overturned and uprooted the entrenched political status quo in Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal and Madagascar. At the very least, they have forced incumbent governments to commit to conducting substantive reforms in Indonesia, Morocco and Peru. Iran seems to be the latest country to be in the periodic throes of Gen Z revolution. Bangladesh travel guides

Each of the Gen Z revolutions are similar if not identical. The root causes that fomented the cascade of revolutions were essentially the same- a large concentration of young men and women in the population, rising poverty levels, soaring inflation rates, a tanking currency, an ever increasing army of unemployed graduates, rampant corruption and institutionalised state sanctioned kleptocracy, stifling authoritarianism, shrinking civic freedoms, oligarchic self-enrichment, institutional hollowing and blatant bad governance.

Add to it the ‘revolution of rising expectations’. Deposed governments such as the one we had in Bangladesh during their initial phase often have invested in promoting literacy, primary and secondary education, expanding primary healthcare provision and social safety nets to the vulnerable and disadvantaged segments of the populace. To top it all, there was an ambitious slew of infrastructure development projects touted as tangible signs of unmistakable progress.

In several instances, it has lifted millions out of the poverty line and had promoted upward income and social mobility. But, it came at a price. Democracy often became the unwitting victim and development was carted around as a credible alternative, citing incongruous comparisons to development outliers. A Faustian bargain was struck with a captive audience. More development at the expense of less democracy and the rest of the country were given no choice, but to indicate mute acquiescence.

This was reminiscent of the ‘decade of democracy’ initiative and the basic democracy experiment of the Pakistani military strongman, Ayub Khan in the late 1950s and much of the 1960s. However, this line of thinking was fallacious at best, pernicious at worst. Corrosion of democracy meant reduced accountability and limited transparency and the blossoming of crony capitalism. State capture of public institutions proceeded apace and cult of personality was meticulously cultivated and inculcated in every walk of life.

Political opposition was neutered and civil society criticism stifled by means fair and foul. The media was co-opted or coerced and state apparatuses lost their original purpose and became organs of the ruling political party. Cultural and religious mobilisation was ramped up by the rulers to acquire greater acceptability and legitimacy in the eyes of the people.

Economic growth and development were used to legitimise a near naked power grab of the state by the ruling party. However, once the economy itself started to stutter and lose steam due to a combination of structural weaknesses and external or exogenous shocks, the enchantment was broken. Disingenuous methods to tide over troubled times included printing more money and thereby leading to runaway inflation or taking foreign loans at steep interest rates from foreign lenders and multilateral agencies.Financial software

This is where the youth, newly empowered with learning and education came into their own. With fewer jobs on offer and higher expectations of better standards of living, the canards of the state were rejected by the young. The very beneficiaries of the fruits of development became its fiercest critics as their worldview had significantly expanded. This was reminiscent of the educated middle class leading the protests on the streets of Tehran during the Islamic Revolution of 1979 in Iran. Ironically, this class had come into its own due to the ‘white revolution’ of the 1960s ushered in by Reza Shah to foster more inclusive development in the country.

The means of effective organised street protests and widely visible resistance was the ubiquitous social media –ironically the fruits of the much touted ‘digital revolution’ initiated by the autocratic dispensations themselves to wow their cowered citizens. It also helped that most of the regimes that were overthrown in the Gen Z led revolutions were on the wrong side of the geopolitical divide because of their uncomfortable proximity towards China/Russia (at times India) and acrimonious or strained relations with the US led western global order. This implied that in many instances, American and western funded NGOs and civil society organisations played a critical role in marshalling the protests with the stated objective of restoring democracy.

Despite actual or alleged allegations by ousted governments, of covert intervention by foreign powers to launch Gen Z revolutions to suit their own geostrategic objectives, on sifting through the evidence, one reaches the incontrovertible conclusion that most of the drivers behind youth driven anti-government movements in recent times were of a home grown variety. When aspiration of the youth for a better tomorrow is thwarted, the rumble of revolution will be heard over and over again.

THERE is no fairytale ending for Gen Z revolution after the storming of the proverbial Bastille. Caretaker or interim governments are hastily formed or cobbled together to steer the revolution ravaged countries through the tortuous transition phase. A cabal of expats, retired technocrats and civil society notables are usually drafted in to right the wrongs of the past and to pave the road to a better future. Reform becomes a byword, reset becomes a mantra, and rectification becomes an obsession. At times, a clean break with the past-the good, the bad and the ugly are attempted. Starry eyed diplomats, usually from the western hemisphere become vociferous champions of the quixotic attempt at forging ‘a brave new world’.

The ability to agitate or propagate rarely translates into administrative nous and competence. Such has been the fate of many of the administrative setups tasked to oversee the transition. Governance by social media fiats and generating actual or virtual support becomes the marker of popular endorsement. The caretaker’s reliance on fringe groups either or both coming from the extreme right or left increases markedly. In a neat quid pro quo, the fringe groups try to dictate policymaking brazenly or insidiously. A campaign of ‘us v them’ is diligently initiated where members of religious, political and cultural minority are scapegoated or labelled as potential fifth columnists.

Despite an overwhelming support initially for the transitional governments, in most cases their performance had or have been underwhelming. Lawlessness, mob violence, factional fighting, rising religious and political intolerance, vendetta driven score settling have travelled in the wake of post-revolutionary regimes. An inability or unwillingness to rein in the mobs result in various vested interest groups exerting disproportionate influence on national policymaking by their sheer ability to organise in large numbers and blackmail the caretakers.

Often, elements within the government themselves rely on the mobs to shore up support and dissuade criticism and opposition. They are ardent students of history as they are inspired by the precedents of the Bolsheviks whipping up the masses to frenzied hysteria during and after the Russian Revolution or the Red Guards used by Chairman Mao to pulverise dissent during the cultural revolution in China. A disparate patchwork of young leaders of the revolution, religious groups and the mob are used as ‘enforcers’ to protect the revolution from actual or imagined threats from internal saboteurs and malevolent external designs of hostile powers. Excesses committed in the name of revolutionary zeal are condoned or winked at. Jingoistic ultra-nationalism is often a byproduct of nationalism where a particular community or group or country is painted as the enemy and is used to deflect attention from internal failures of governance.

Polarisation continues instead of attempts at unification. Rhetoric and populist pandering are given precedence ahead of statesmanship and nation building. Retribution is given pride of place instead of reconciliation. Economic ills have been hardly addressed beyond cosmetic measures and shattered economies have been momentarily propped up by liberal doses of foreign loans. Much vaunted pro poor and pro people policies sound too good to be true and in most cases, that’s exactly the case. Ordinary people continue to be battered by the ravages of unchecked inflation and fear for the security of their lives and property. The biggest segment of the revolution-ordinary students feel cheated and find little that they can relate to with the new Gen Z leaders claiming to pontificate on their behalf.Financial software

Another truism of revolution also emerges-those who acquire power from tyrants very soon exhibit the same intolerance and lash out in fury at criticisms targeted at them. The oppressed turn into the oppressors. The very champions of free speech, accountability, good governance and democracy bristle in rage when their methods are challenged. Stint in power often breeds arrogance, which in turn leads rise to hubris. An inability to acknowledge one’s faults or owe up to their mistakes seems to be emblematic of those ensconced in authority. Course correction is rarely attempted, which often leads to disastrous consequences for the polity and the nation.

Scientists claim that cockroaches can survive nuclear Armageddon. Probably this is also true in politics as well. A remarkable bunch of resilient people manage to reinvent themselves as arch revolutionaries as they effortlessly shed the image of craven sycophants and toadies of the deposed tyrannical regime. Such is their ingenuity and utility that they manage to wriggle their way into positions of trust and responsibility even under the new dispensation, thus ensuring their continued relevance. Probably they have Talleyrand, the great French diplomat as their role model, who was known as ‘the great survivor’. He had held high office under the monarchy of Lois XVI, the French revolution , the reign of Napoleon Bonaparte, the Bourbon Restoration and the July Monarchy-a whopping five regime veteran. His public views were elastic and bended in the direction in which the political wind blew.

Selective freedoms have been achieved for various revolutionary groups at the expense of the enforced quiescence of the dissenting voices. History that had been officially curated and narrated by the deposed regimes have been reinterpreted, not necessarily to be more accurate but to suit the worldview of the incumbents. The old guard have been replaced by the ‘Young Turks’ – the vanguard and the self-appointed custodians of the revolution, who now claim a permanent place at the high table. Loud whispers of venality and self-enrichment dog many of the newly minted heroes of the revolution, thereby taking the gloss of the revolution in the eyes of the previously adoring public.

THE vanguard of change-the Young Turks of the Gen Z revolution, would do well to remember the fate of the original Young Turks at the turn of the twentieth century in the Ottoman Empire. In the name of securing greater freedom and equality from the oppressive rule of Sultan Abdul Hamid, they ushered in a revolution. However, all it succeeded was irreparably damaging the multicultural, multiethnic fabric of the Ottoman Empire and bringing in a narrow Turkish ethnic identity which alienated the rest of the non-Turkish inhabitants of the empire. Their foolhardiness in rushing into the first World War in pursuit of recovering lost glory resulted in the defeat and ultimate disintegration of the six hundred old transcontinental Ottoman Empire.

The promise of change that was both exhilarating and intoxicating at the onset and had swept the masses along in messianic fervour have often failed to materialise in real life. Lofty claims of reducing or removing impediments and institutionalised obstacles to political, economic and social inequity have proved to be hollow and misleading. It has bred simmering dissatisfaction and creeping disillusionment amongst the long suffering masses who have not visibly witnessed tangible improvement in their everyday lives.Financial software

A textbook case has been the monumental betrayal of the hopes and aspirations of the ordinary Iranians after the Islamic revolution in Iran during 1979. A narrow coterie of self-serving religious preachers seized power aided by the cold messianic charisma and cunning of Ayatollah Khomeini and systematically silenced all dissenting voices and hunted down dissidents. Instead of securing genuine democracy for the masses, an oppressive system was put into place. The state surveillance became even more pervasive and entrenched than that of the deposed Shah and his Savak henchmen. The clock on modernity was wilfully turned back as Iran descended into medieval retrogression. Women were deliberately demoted in social and political standing and their right to self-determination was restricted. Sartorial choice of women and even men became regulated by the state. A cycle of interminable conflict and bloody war, foreign isolation, international sanctions, regional meddling, ruination of the domestic economy and periodic suppression of political and social uprisings followed. Millions of bright, educated, skilled Iranians have fled the country. Iran continues to writhe in agony from periodic revolutionary convulsions. The children and grandchildren of revolutionaries have turned into its bitterest opponents.

Periods of transition are admittedly chaotic and messy as there are no predefined roadmaps to fall back upon. It takes near superhuman attempt to undo decades of institutional rot and weed out systemic corruption. Under the best possible outcome, revolutions yield real meaningful changes that are beneficial to the common lot such as certain redeeming aspects of the French revolution which reduced greatly or removed feudalism and absolutism from the French body politic. It could also yield a Mandela like figure, who would lay out the imperfect yet inclusive road map for South Africa to become a rainbow nation after decades of dehumanising apartheid rule. In terms of less desirable trajectories, it could morph and atrophy into the Iranian revolution post 1979, where select group of Ayatollahs and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps could hijack the revolution and impose a regime that is far more oppressive and restrictive than that of the Shah of Iran. The worst possible scenario would be akin to the fate of Egypt after the Arab Spring. Mubarak’s corrupt regime was overthrown through the movement that gained steam at Tahrir Square at Cairo followed by the incompetent, fractious government of Morsi only to be upended by army rule under General Sissi. All the bloodshed and sacrifice during the Arab Spring uprising amounted to naught.

Every revolution carries within itself the seeds of its own destruction. Many revolutions across time have atrophied or sidetracked or have lost support of the very people that they claim to represent. Counter revolutions and power grab by strongmen usually occur when the ordinary folks weary of the unending chaos and lawlessness. At best, they become diluted and become pale imitations of the original, derided and rejected by most stakeholders.

It is imperative that the core objectives of the Gen-Z led revolution that inspired countless of their fellow citizens to throw in their lot with the revolutionaries be respected and upheld. It should be noted that millions of countrymen are also watching and want the revolution to succeed. The price of failure is too high for the country and its citizens. Much like the fictional character, Boxer, the indefatigable, bold, selfless horse from Orwell’s Animal Farm, the people (the old, the young, the infirm, the strong, the men, the women, the children, the majority and the minority) provide the motive force for a revolution. Their will and their aspiration need to be recognised, respected and implemented. A revolution cannot be the exclusive property of one single demographic group or of one particular religious persuasion. It cannot serve to alienate or marginalise large segments of the population. If that were to happen, the sacrifice of the heroic souls who perished opposing tyranny would be in vain. Just like Boxer in Animal Farm.

Parvez Karim Abbasi is the executive director at Centre for Governance Studies and assistant professor of economics at East West University.

This article was originally published on Newage.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.