The Making of Ukraine

Tim Black | 09 January 2023

Russia's brutal invasion has revealed the depth and strength of Ukrainian nationhood.

On 24 February 2022, the world changed in ways with which we are still to come to terms.

That, of course, was the day Russian president Vladimir Putin launched the invasion of Ukraine. ‘I have decided to conduct a special military operation’, he said, sat at a desk in the Kremlin, a Russian flag behind him.

It was scarcely believable, even as Russian tanks and personnel carriers began rolling across the border with Ukraine. Of course we knew there had been a months-long military build-up near the Ukrainian border. And we knew there were pre-existing tensions, fuelled in large part by Western actions over several decades. There was the expansion eastwards of NATO, that hoary old relic of the Cold War. There was the Euromaidan revolution in 2014, in which Ukraine’s democratically elected, pro-Russian president was deposed after violent, popular protests against his backtracking on closer EU participation. And since 2014 there had been intermittent conflict in Ukraine’s east over the self-declared People’s Republics of Donetsk and Luhansk.

Yet the idea that Russia would actually invade the largest country in Europe, with a population of over 40million, still seemed outlandish. Even for many Ukrainians. In late January, Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky gave a press conference in which he attacked ‘Western alarmism’ over Russia’s military posturing near the Ukrainian border. And in early February David Arakhamia, the head of Zelensky’s Servant of the People party, said Western media outlets peddling ‘hysteria’ about a possible war were more of a threat to Ukraine than Russia’s state media.

And then it happened. Putin launched a full-scale invasion of a sovereign nation in the heart of Europe.

Few outside Ukraine gave it much of a chance. Putin clearly expected a quick, easy victory. Leaked Russian military plans show generals expected the Russian army to triumph within days. Officers were even told to pack their dress uniforms and medals for the anticipated military parades in Kyiv.

Putin’s confidence of a quick Russian victory was clearly shared by many in Washington. Just days before the invasion, US general Mark Milley, the chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said it was possible Kyiv could fall within 72 hours. Perhaps that explains why, a couple of days into the conflict, America offered Zelensky a chance to evacuate.

Zelensky’s defiant response to that offer – ‘The fight is here; I need ammunition, not a ride’ – provided a clear sign that both the West and Russia had completely misjudged Ukraine. They had assumed that Ukraine was too weak and divided to withstand the might of the Russian army. They had assumed that Zelensky, whose domestic popularity had slumped during 2021, would be all too ready to cut and run. And above all they assumed that, in the words of Putin, ‘there was no Ukraine’. That Ukrainians had no real sense of nationhood. And that they would be willing to accept that Russian might was right.

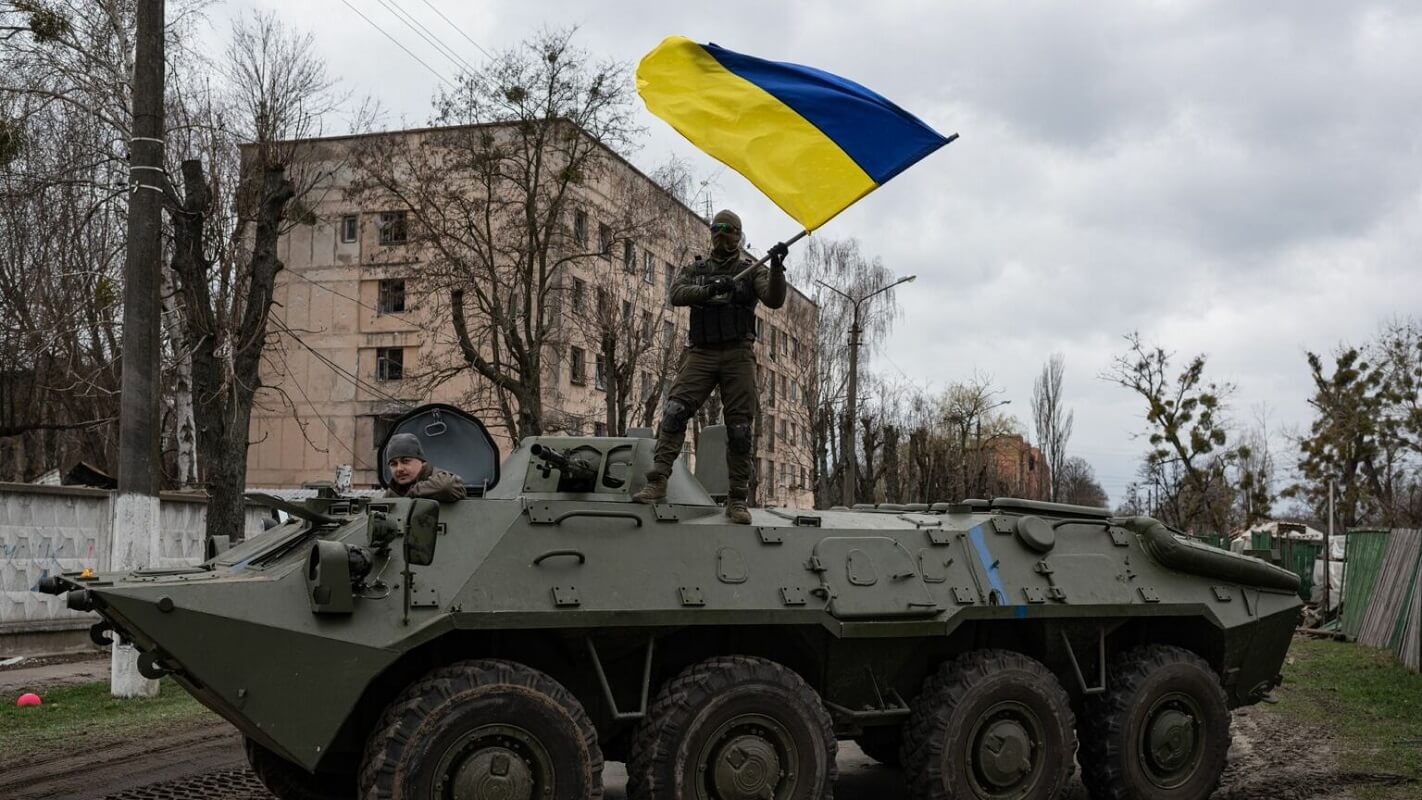

How wrong they were. From 24 February onwards, the Ukrainian resistance has been formidable. Ukraine’s forces have demonstrated the depth of Ukrainian nationhood through the sheer ferocity of the fightback. Thousands upon thousands quickly volunteered to fight alongside the Ukrainian army – which was already much enlarged and better trained than it was in 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea. Their successes during the early stages of the conflict were striking. Russian forces, nestled in the outskirts of the capital of Kyiv, were forced to retreat by the beginning of April. Russia’s attempt to take the port of Odesa stalled at Mykolaiv. And then, in May, the Russian military was pushed out of the second-largest city, Kharkiv, in eastern Ukraine.

Following these Ukrainian victories, the Russian military changed tack. It focussed instead on grinding out slow, attritional territorial gains in Ukraine’s east. And for a while the tide did seem to be turning in Russia’s favour. But it was short-lived. In September, the Ukrainian military made spectacular gains, retaking some 6,000 square kilometres in a matter of days. And then, in November, Ukraine re-took Kherson, the only regional capital the Russians still held. As it stands right now, Russia’s anticipated days-long military conquest has turned into a months-long humiliation.

But the success of Ukraine’s resistance, the sheer courage and bravery of the Ukrainian people, testifies to more than its military prowess, as impressive as that has been. It testifies also to Ukrainians’ deep attachment to the very thing Putin rubbished. An attachment to their way of life as Ukrainians, their basic freedoms as members of a democratic, sovereign nation. That’s what both Moscow and Washington underestimated – the strength of Ukrainian nationhood.

This sense of nationhood, unity and resolve has not always been there, of course. Even less than a decade ago, divisions were still pronounced – between west and east, Unitary Orthodox and Russian Orthodox, Ukrainian-speaking and Russian-speaking. But as Russia has threatened Ukraine in recent years, so Ukrainians’ sense of themselves as Ukrainian has spread and deepened. All available surveys show this same pattern, of a growing sense of loyalty and attachment to Ukraine – even in the east, where pro-Russian sentiments have always been more prevalent.

Indeed, in late October, survey data showed that Ukrainians were more determined to defend their nation than ever. In total, 86 per cent of respondents favoured continuing armed resistance over making peace and offering concessions to Russia – this included 66 per cent of Ukraine’s Russian speakers. And this is because being Ukrainian – being a free citizen in a democratic, independent nation – now really means something. It matters. It is something worth fighting for.

Not that everyone in the West is willing to recognise the Ukrainian resistance for what it is. For some on the ‘anti-war’ left and right, the war in Ukraine is now just a proxy war, in which Western powers are using Ukrainians for their own nefarious ends – to attack Russia, to bolster their domestic authority, even to find something else to ‘fight’ after Covid. This self-styled pro-diplomacy clique even continues to insist that the West and NATO are the main antagonists in this conflict. As if Russia was effectively forced by the West’s actions into invading Ukraine. As if NATO made Putin do it.

This is upside-down thinking. It attributes far too much power and foresight to Western leaders, and ignores the extent to which they were, at first, reluctant to support Ukraine. Think back to President Biden’s willingness to tolerate a ‘minor incursion’ on the part of Russia into Ukraine. Or think of the continued reluctance of NATO members to send more ‘offensive’ weapons to Ukraine.

And this thinking also fails to attribute responsibility for the war to Russia. Putin is the aggressor here. It was his tanks and artillery that rolled into Ukraine on 24 February. It is the Russian military raining missiles and drones down on Ukrainian towns and cities day after day.

Above all, those in the West cynically dismissing Ukraine’s resistance as a proxy war fail to attribute any agency to the Ukrainians themselves. At best, they’re seen as dupes, sacrificial lambs in just another Western intervention into a sovereign nation, like Iraq, Afghanistan or Syria before it. This fundamentally misunderstands the extent to which it is Ukraine’s needs and objectives, and not the West’s, that are directing the resistance. It is their desire to defend what matters to them – their entire way of life as Ukrainians – that is driving the resistance on.

Yes, the West has given Ukraine billions of dollars’ worth of weaponry. But it is the Ukrainians themselves who are quickly and determinedly absorbing this bewildering array of hi-tech kit – because they want to realise their objectives.

Indeed, over the past year, far too much importance has been attached to the weapons the West is providing. After all, a similarly advanced armoury provided by the West didn’t help the Afghan security forces fight off the Taliban back in August 2021. That’s because those hapless soldiers and policemen lacked what the Ukrainians have in abundance – a deep, moral commitment to their nation. A determination to defend it. And a willingness to die for it.

This war has upended many long-held assumptions. About lasting peace and stability in postwar Europe. About the overwhelming strength of the Russian military. And, above all, about the demise of the nation in a globalised world. For in eastern Europe right now there are millions prepared to suffer and fight for exactly this. The nation – the nation of Ukraine.

Tim Black is a spiked columnist.

This article was originally published on Spiked.

Views in this article are author’s own and do not necessarily reflect CGS policy.